The sacred geometry of the Mandala: How structured complexity can be as clear and compelling as extreme simplicity

“It is not what you are telling people, it is how you are saying it.“

― Nassim Nicholas Taleb

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable

Have you been feeling the swirl of information overload, in a world where what we see and hear is harder and harder to trust?

Today’s world is increasingly interconnected and biased for speed. This has serious consequences on how information impacts us. Couple that with the yet unknown long-term effects of AI, and the question is: how do we function as responsible curators and stewards of information?

Legibility and understanding is often conflated with simplicity. In our urge or encouragement to go fast, we forgo context and nuance for simple binary answers and summations, mistakenly thinking it automatically brings about clarity and understanding.

We see it daily. We see it in the constant drive to reduce friction in UI/UX, in the powerful push for journalism and analysis to always be “digestible”, and in the collapse of cable news into nothing but incessant opinion and disaster, striving for the common base denominator.

Data vs information

Data in and of itself isn’t necessarily useful. It must be translated into information to get insights from it — and information demands contextualization to be meaningful. For example, imagine you have a list of numbers; 37.2, 98.5, 42.9 etc. There’s no discernible pattern — it’s just a collection of numbers that mean nothing.

But if you are told they represent the temperatures of certain cities, on a particular day, at a specific time of year, now that data has become meaningful information because it has been contextualized.

What is interesting is that how we contextualize and structure and consume information is heavily influenced by the history, traditions, and context of the culture or the organization in which it resides.

In the Western world, we adhere to established norms regarding information hierarchy and presentation, often without giving them a second thought. Our digital devices and metro system signage designs are examples of this, from choosing common fonts and formats for road signs to standardized UX/UI patterns.

However, we have overlooked the fact that older spiritual practices, indigenous cultures, and non-Western civilizations have long maintained intricate and robust systems for curating and disseminating information. Oral traditions, storytelling, hieroglyphics, and ancient scroll formats are a treasure trove of powerful and effective storytelling methodologies. And these traditions do not always communicate in a right-to-left, top-to-bottom, English language kind of way. This opens interesting new possibilities.

So what would happen if we looked to the wisdom and frameworks found in spiritual, non-Western traditions regarding the transmission of complex information? How might one think about integrating the knowledge we can gain by studying the practices of these lineages and the diverse ways in which they handle information into visual communication work in this modern age?

Mandalas and/as infographics

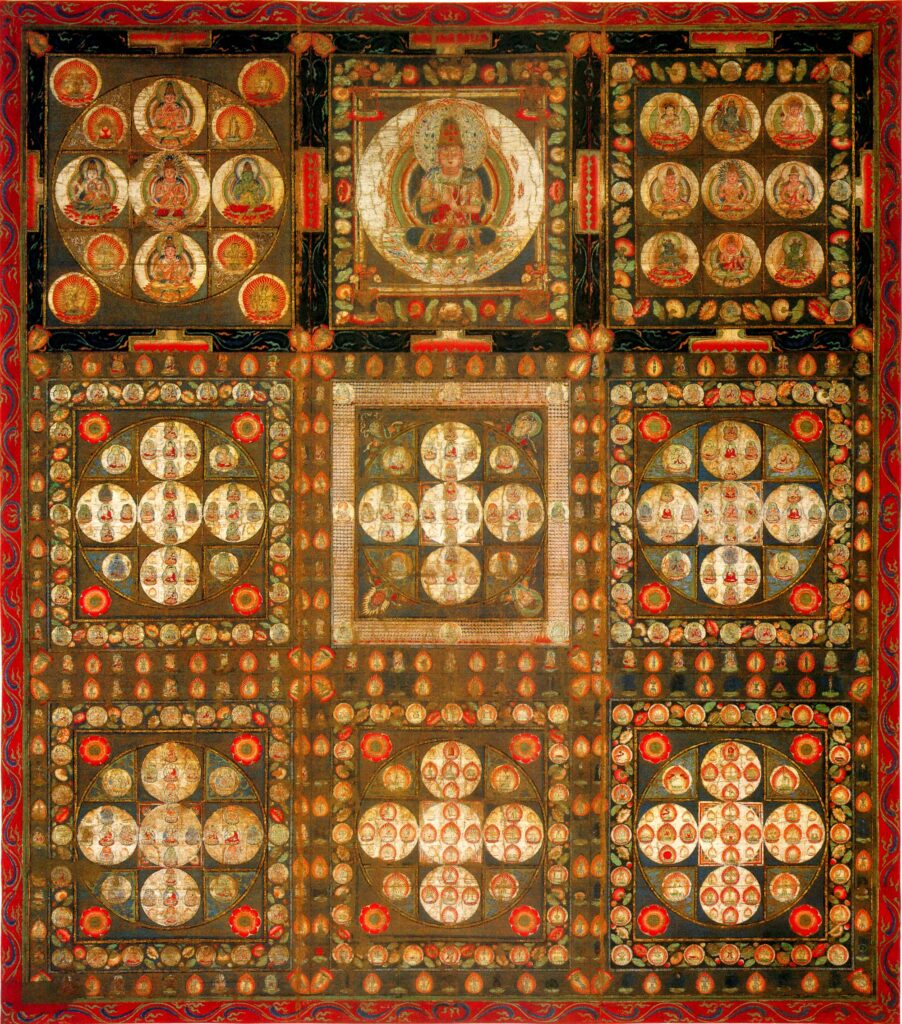

Let’s explore one historic example: the mandala, which originated from 1st century B.C.E. Indian Buddhists.

A mandala is an example of sacred geometry that lays out information visually, with intent and purpose. Not only does complex, sacred knowledge emanate from the center or flow outward from it, but every quadrant and level is filled with detailed, often subtextual or symbolic, content.

The Mandala of Jnanadakini, also known as the Mandala of the Wisdom Dakini, from the late 14th century BCE, hangs in The Met. Here is its official description:

“The central six-armed goddess (devi), Jnanadakini, is surrounded by eight emanations — representations of the devi that correspond to the colors of the mandala’s four directional quadrants. Four additional protective goddesses sit within the gateways. Surrounding the mandala are concentric circles that contain lotus petals, vajras, flames, and the eight great burial grounds. Additional dakinis and lamas occupy roundels in the corners. The upper register depicts lamas and mahasiddhas representing the Sakya school’s spiritual lineage. The lower register depicts protective deities and a monk who performs a consecration ritual. This tangka was likely part of a set of forty-two mandalas relating to ritual texts collectively known as the Vajravali or Vajramala (Garland of Vajras).”

Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37802

It tells a rich and symbolic story rooted in Tibetan Buddhism. This mandala represents the enlightened feminine energy and wisdom embodied by the deity Jnanadakini. The story unfolds through intricate symbols and iconography, each element contributing to the greater narrative of spiritual awakening and enlightenment.

Psychologist Carl Jung is credited with introducing mandalas into modern Western thought, after observing the appearance of circle motifs across religions and cultures. He used the general framework to make personal, exploratory sketches “which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time”. More from Wikipedia:

Jung claimed that the urge to make mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. He further hypothesized their appearance indicated a ‘profound re-balancing process’ is underway in the psyche; the result of the process would be a more complex and better integrated personality.

—Wikipedia

And…

The mandala serves a conservative purpose — namely, to restore a previously existing order. But it also serves the creative purpose of giving expression and form to something that does not yet exist, something new and unique.

— Marie-Louise von Franz, In Man and His Symbols (C. G. Jung, Ed.)

A picture, a story, a kind of map to the unknown — a mandala is all of these things. Mandalas see information as a connected web, containing both personal significance and profound, esoteric understanding. They operate not just on an intellectual level, but also on a somatic one. Those who engage with mandalas often describe how they are able to retain the intricate details of its structure the longer they meditate on it. It is not just an object to be seen; the mandala requires one’s focus and presence to truly appreciate it. A mandala is immersive.

For example, the story told by the Mandala of Jnanadakini is one of transformation and spiritual ascent. It guides the practitioner from the outer layers of ordinary reality through progressively deeper levels of understanding and experience, culminating in the realization of the wisdom embodied by Jnanadakini.

- Outer layer: Represents the worldly existence and the beginning of the spiritual journey. Practitioners are reminded of the distractions and delusions that they must overcome.

- Middle layers: Symbolize the stages of purification and meditation. Here, practitioners work on developing virtues such as patience, concentration, and insight.

- Inner layer: Represents the direct experience of wisdom and the realization of the true nature of reality. This is where the practitioner encounters Jnanadakini and integrates her wisdom into their being.

‘Digestible’ vs useful

It bears consideration; in a world where we, as visual communication experts, are often trying to make information digestible’ and ‘nuggetized’ — how might we strike a balance between storytelling, complexity, and understanding?

It is human nature to desire the simplest answer, often a binary one of “this is good and that is bad” or “do this, not that”. We’re frequently avoidant of complex information, or we desperately try to simplify complexity to the point that it negates all the meaning and helpful nuance, and in turn creates more misunderstanding and disconnection.

The mandala demonstrates the ability to trust an audience to embrace some complexity. And again, this complexity does not have to equate to a lack of comprehension. That is the binary trap mentioned earlier. What makes the complex legible is the editing, hierarchy, and structure of said information, and this is where we could learn by taking inspiration from these more esoteric structures.

And, in a world where we’re increasingly required to question everything we see and hear moving forward, is there not value in embracing some complexity? In returning to some of the old ways, which are immune to the whims of technocrats, and instead call us to communicate with respect and nuance?

The above infographic from the magazine Slow Journalism may not be as intricate as a traditional mandala, but it embodies the same principles. The reader uses the headline and subhead to gain initial context, and then is immediately guided to the giant purple NOV element as the starting point.

There is a lot going on here. The “How it works” key is there to explain the color coding and categories, and the measures of “time of awareness” clearly labeled. Data is laid out clearly and the reader is then given the opportunity to make the links between the data points and consider the visual in its totality. In doing so, context, interconnections, new thoughts and ideas are borne, making the experience personal and enriching.

Attention and opportunity

Milarepa, a Buddhist yogi and poet once said, “A song may be beautiful, but without understanding its meaning, it is just a tune.”

In today’s information-saturated world, our attention is valuable. It is consistently being commoditized, exploited, and leveraged in ways that do not nourish us. Promoting mutual understanding through effective storytelling within large and distributed organizations is going to be the biggest challenge facing us in the coming decades.

This quest for clarity and simplicity should not be at the expense of nuance and detail. Often the real story lives between the lines, in the liminal spaces that are rich with opportunity for innovation. This is where using less common, ancient frameworks which were “battle-tested” for millenia can help us create visual artifacts that are both organized, informative, and encourage people to dive a little deeper.

Visual: “The Mandala of the Diamond World” is a Japanese hanging scroll from the Kamakura period, roughly the 15th century CE. It represents the Buddhist spiritual universe and its realms and deities.