The unexpected origins of 17 words and phrases we use every day

One of the many important reckonings of the Black Lives Matter movement is a reconsidering of the language we use in our everyday lives—and in our work every day. This is a large set of terms and phrases informed by time, habit, and thoughtlessness.

Just as realtors and architects are substituting “Primary Bedroom” for “Master Bedroom“, artists, visual designers, and computer scientists also are making changes. To be clear, these changes mean little without other, bigger, systemic changes happening as well. Less divisive semantics won’t kill racism, but it’s a piece of the puzzle.

For every obviously problematic idiom or phrase like “open the kimono” or “off the reservation“, there’s something silly like “giving 110%” or brainy like “think outside the box“. And 2020 has seen many articles and opinions on historically racist phrases such as sold down the river, cakewalk/take the cake, peanut gallery, and “no can do” (alas, Hall & Oates). But stupid business cliches are one thing and the historical etymology of common words is another.

That said, not all the terms below have terrible origins—some are just… interesting. So here’s a taste of the history behind some words and phases that designers, business people, and others may find themselves using nearly every day.

- Alarm | Rooted in violence and war. Being woken by a braying alarm in the morning can be a violent, undesirable thing for many. But not so violent as the word’s origin. It comes from the Italian battle cry “all’arme!”. Translation: “to your weapons!”, or, simply, “to arms!” Over time it shifted to be a warning in and of itself, as well as to name the object used to sound it. Regardless, its origins are decidedly more violent than how we typically start our days.

- Avant Garde | Rooted in violence and war. This one comes from the French language and literally means “advance guard” (similarly, vanguard), though originally in a military sense. In the early 20th century it was coopted by the arts world to represent artists or works characterized by “aesthetic innovation and initial unacceptability”, according to Wikipedia. In fact, design hero Herb Lubalin loved the idea so much he named both a magazine and a typeface after it.

- Barking up the wrong tree | Rooted in hunting. This idiom became common in 19th century America. It references a hunting dog chasing down raccoons, which often climb a tree to escape. While the dog is supposed to remain at the base of the tree until its owner arrives, sometimes the nocturnal rodent would leap or scurry to a branch on a close-by tree, escaping. So the common usage of mistaking one’s goal, or pursuing the wrong course, is a clear parallel to the original meaning.

- Brand | Rooted in Old English. It first meant fire, but by the 1500s it was more specifically referring to a mark made by a hot iron (such as on a cask). In the early 1800s it came to mean the tool itself, as well, and by 1854 “a particular make of goods”. The Online Etymology Dictionary says that “brand name” has been used since 1889 on and “brand loyalty starting in 1961.

- Clue | Rooted in Greek mythology. 500 years ago the word in Middle English was clewe or cleue, meaning a ball of thread or yarn. Its meaning of “that which points the way” is a 17th century shift referring to the clew of thread Theseus gave to Ariadne so he could find his way out of the Labyrinth.

- Deadline | Rooted in violence and war. It seems this term came into use in POW camps during the American Civil War, a far cry from journalists’ time limits or delivering client work. The line was much more literal: “a line drawn within or around a prison that a prisoner passes at the risk of being shot”—a real “dead line”, according to Merriam Webster. It’s amazing how usage can shift so much.

- Gradient | Rooted in Latin. In 1835 it meant the “steep slope of a road or railroad”, from the Latin gradientem, the present participle of the word gradi, “to walk.” But it must’ve been the sense of gradual change that lent the word to the design world, because the Medieval Latin word gradualis (itself from the Latin gradus, which meant “a step; a step climbed; a step toward something, a degree of something rising by stages”) is more in line with the color transitions we’re talking about.

- Grid | Rooted in cooking. This is a shortening of gridiron or griddle, historically a designed or symmetrical cooking tool used in or over a fire. The rack on your charcoal or gas grill is essentially a gridiron. But… before its association with city planning, American football, and graphic design layouts it was also a medieval torture device on which people were tied so they could be burned alive.

- Hierarchy | Rooted in religion. Before its visual design sense, in the 14th century it meant “rank in the sacred order; one of the three divisions of the nine orders of angels”. It’s from the Greek hierarkhia: “rule of a high priest”.

- “I call shotgun” or ride shotgun | Rooted in violence. Stagecoach drivers in the early days of the American West wanted protection—so they literally had an armed guard riding up front in order to scare or fight off bandits who might attack them (or, of course, Indigenous people protecting their lands).

- Indigo | Rooted in Greek. This color ranges from a deep violet blue to a darker, grayish blue. Comes from the Greek indikon, meaning “blue dye from India”, or, (apparently) more literally, “Indian substance”.

- Master & slave | Rooted in slavery and racism. Clearly, the “master” and “slave” terms used by photographers, engineers, and coders to note which main flashes trigger other secondary flashes, or simply which software and hardware components control another, are (and always have been) problematic. To think that they’ve been used so carelessly for over half a century is mind-boggling. The word slave itself came from early Europe’s, North Africa’s, and the Middle East’s long history of forcing people to work without pay. Many slaves were captured from eastern Europe—the Slavic peoples. Though there’s a lot more to it, the name stuck. Even master and masterpiece, historically associated with skill rather than power, are coming under scrutiny.

- Pamphlet | Rooted in a Latin love poem. A pamphlet typically was/is a single sheet of paper printed on both sides, sometimes folded in ways that make it booklet-like. Wikipedia says, “Pamphlets functioned in place of magazine articles in the pre-magazine era… They were a primary means of communication for people interested in political and religious issues, such as slavery. Pamphlets never looked at both sides of a question; most were avowedly partisan, trying not just to inform but to convince the reader.” The word came from a single, famous, much earlier product: a short but popular 12th century Latin love poem called “Pamphilus, seu de Amore” (or, “Pamphilus, or about Love”). The word became the Anglo-Latin panfletus, from Greek pamphilos which meant “loved by all”.

- Pioneer | Rooted in conquest and war. Originally defined in the 1500s as “one of a party or company of foot soldiers furnished with digging and cutting equipment who prepare the way for the army”. It comes from the Middle French pionnier (foot-soldier, military pioneer), itself related to peon/pawn. The figurative sense arrived shortly after, in the 1600s, with the meaning “a first or early explorer”.

- Raise the bar | Rooted in track & field. This idiom is directly related to the high jump and pole vault, both of which get progressively more difficult and impressive as you’re required to propel yourself higher and higher. It became popular in the early 1900s.

- Robot | Rooted in Slavic. As explained above, the word slave came from the pre-African slave trade in Slavic people. So it’s awkward to learn that the word robot comes from the Slavic language (via an early sci-fi novel): “from Czech robotnik ‘forced worker,’ from robota ‘forced labor, compulsory service, drudgery,’ from robotiti ‘to work, drudge,’ from an Old Czech source akin to Old Church Slavonic rabota ‘servitude,’ from rabu ‘slave’.”

- Silhouette | Rooted in a namesake. Étienne de Silhouette was the French minister of finance in mid-1700s who, due to the expensive and unpopular Seven Years’ War, imposed harsh austerity policies. Ultimately this simple, inexpensive way of capturing someone’s likeness (as opposed to expensive, life-like, painted portraits) became associated with him—and even today those profiles in shadow are called silhouettes.

Words are complicated. People more so. The American who coined the term “racism” in 1902 in order to argue against the evils of racial segregation also advocated for the re-location and re-education of Indigenous peoples by saying, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man”.

No word, phrase, logo, or even children’s song should be safe from review and reconsideration (however you look at it, “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe” has quite a heritage for it to be so popular amongst children). Meanings certainly can change over time, but the fact is that time is what made lots of racist words, phrases, and sports logos nearly invisible to many people until recently. So when time isn’t acting as the great equalizer, people must.

There’s probably no end to what you can learn (and learn from) when you use a little empathy, curiosity, or critical thinking to look deeper.

How we speak is a great place to start.

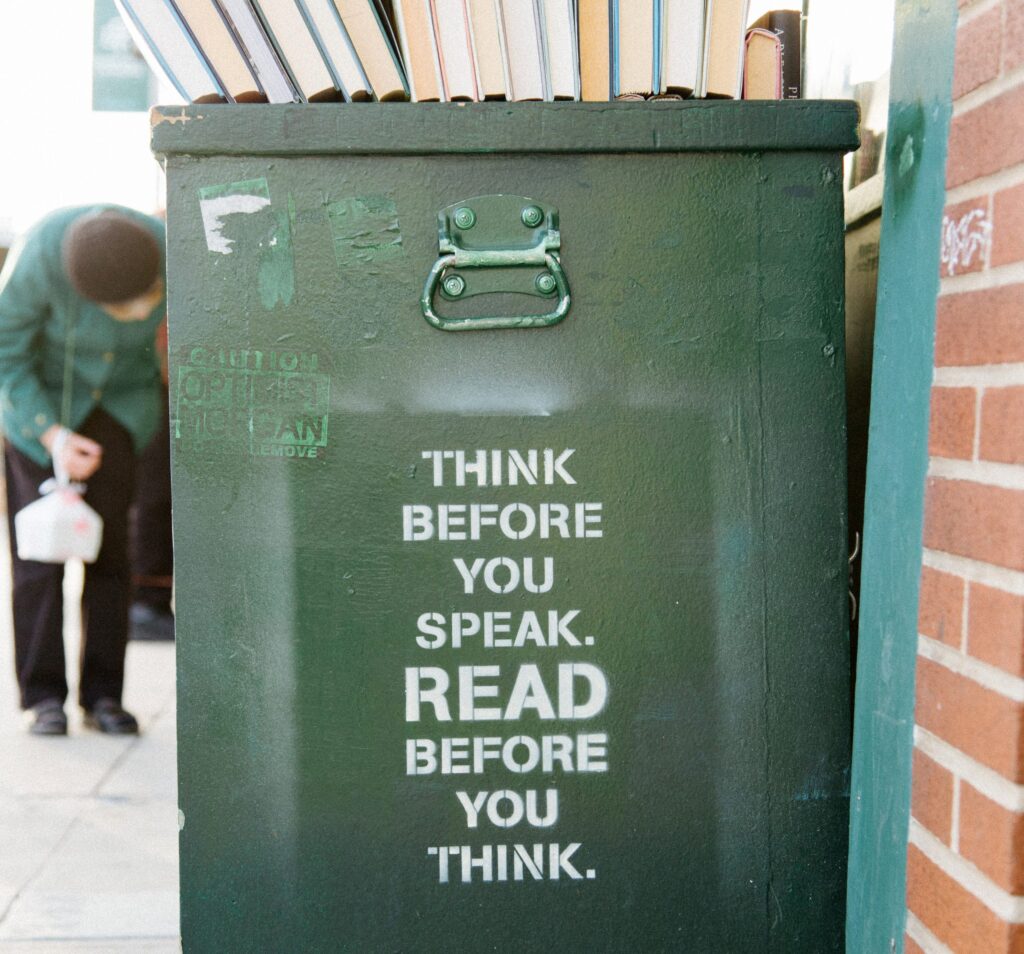

Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash.